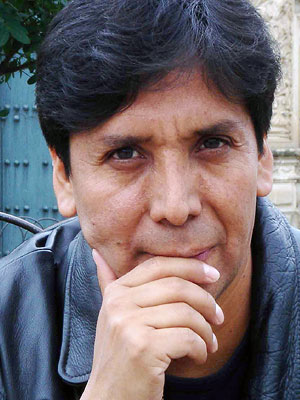

Odi Gonzales Book Reviews

BIRDS ON THE KISWAR TREE

Odi Gonzales’s Birds on the Kiswar Tree (2014, 2Leaf Press), with both the author’s Spanish originals and English translations by poet Lynn Levin, presents to the Anglophone reader vivid documentary poetry of the painted world of colonial-era Quechua artists. Birds on the Kiswar Tree would be a welcome addition to a book shelf of those with an interest in Peruvian Andean cultural identity, ekphrastic poetry, and the literature of resistance.

Born in Cusco, Peru himself, Gonzales explores the subversive art of Quechua painters, who later became known as the School of Cusco painters, as many of them resided in or near Cusco. During Peru’s colonial era, the Spanish attempted to evangelize the Quechua people by teaching them how to paint fine art while enforcing the European artistic styles and restricting the subject matter to the Christian religion. However, the Quechua painters rebelled against this artistic colonization by adding Andean details–such as native flora and fauna–in their paintings. The painters’ legacy lives on, but many of them were illiterate, and, therefore, their names are unknown. Gonzales lends his voice to these painters and brings light to the art of resilience in the time of oppression; Levin acts as his partner to unveil his rendition of their art to the English-speaking world.

Even if the reader does not enter the poetry collection with knowledge of Peruvian art history, the poems create a hospitable space in which the reader can learn and understand their specific heritage. The titles of the poems are, in fact, the titles and locations of the actual paintings, and many poems include explanatory notes at the end. The poems inform us without the impulse to educate overwhelming the pages. “Adoration of the Shepherds” clearly portrays the scene in the painting:

A thicket of cloud covers

the constellations of the hummingbird

and the flock of llamas

in heat

In the manger…the cave of Rayampata?

[…]

The Virgin

the Child and the angels glow

with a sweet and simple beauty:

one of the delights

of Cusqueñan art

Lamb of God

Son of Man

the newborn has

two whorls in his hair:

the mark

of one who will be stubborn

In this poem, one can see how the popular Christian theme was refashioned by the painter (Francisco Chiwantito) to place the figures in a specifically Andean location. According to the translator’s note, the Quechuas also believed that two whorls in hair meant stubbornness–one can imagine Chiwantito adding that belief as a means of rebelling against not only the colonizers’ artistic style but also religion. The italicized parts of this poem function as explicatory comments, like those one would hear from an audio guide in a museum, which heighten the effect of seeing Birds on the Kiswar Tree as a poetic gallery. Italics appear in other poems throughout the book, and sometimes, they act as another voice, an outsider’s voice, removed from the life of the painting. For instance, in “The Expulsion from Paradise,” the italicized portion exclaims: “we hereby command you may paint / only what the Scriptures say.” In spite of the pellucid nature of the narrative, the poetry still retains exciting mystery that allows the reader to fill in the gaps (the indentations in the poems seem to invite this effect as well). “Apprentice Painters” tugs the reader into a haze of birds:

The signature of the artist lies

hidden

on the back of the canvas

in a ribbon that hangs

from the beak of a bird:

a wanchaco?

a zorzal?

a calandria?

The reader may not know what a wanchaco or a zorzal is, but understands that they are birds native to Peru. The bright birds that occupy many of the poems in the collection seem to be anchors, agents that keep the poetic space in Peru while the linguistic landscape shifts.

Close poet-translator collaboration and painstaking research of the original language and culture, make Birds on the Kiswar Tree a truly animated documentary of painters who found escape from foreign domination through art.

PER CONTRA: (Issue 35, 2015) Emily Yoon

REVIEW OF BIRDS ON THE KISWAR TREE BY ODI GONZALES

“The Apu Pachatusan is angry.” That was the first sentence I was taught to say when I studied Quechua in Cusco, Peru– and not quite what I expected from an introductory language lesson. The Apus are the mountain gods of the indigenous peoples of the Andes. They are the Andes, personified; honored by the Inca, they are still very much alive in modern Andean tradition. In Cusco, I found, you always live in their literal and metaphorical shadow, so fundamental to culture and language that they make their way into a level one Quechua class and into day-to-day conversation. People leave them offerings just as they pay homage to Christ and to the Virgin. This is the sort of powerful syncretism that lies at the heart of Odi Gonzales’ Birds on the Kiswar Tree, a luminous collection of poems based on subversive and syncretistic church art. It comes to us in an outstanding translation by poet Lynn Levin.

I very vividly remember my introduction to the paintings of the Cusco School, the art that inspired the poems of Birds on the Kiswar Tree (originally titled La Escuela de Cusco). In a museum in Cusco, I wondered over the colorful, vibrant portraits of Mary and the Archangels. I remarked on their unusual shape; garbed in flowing robes, they look triangular, almost like mountains themselves. My tour guide gave me a crooked smile and said, “You don’t really think that’s a coincidence?”

This style of art, which allowed the saints and angels of the Christian tradition to be reimagined as mountain gods, comes from a particular historical context. We don’t often think of artists as evangelizers, but in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, prominent painters from Europe arrived to teach painting to the indigenous people of Peru, and, by doing so, indoctrinate them into Catholicism. These indigenous painters were given the tools that they needed to create gorgeous, enduring works of art, but were not allowed much freedom of expression. They were only permitted to paint religious subject matter, as we see in Gonzales’ “Expulsion from Paradise”:

But, as you would expect, artists are often adept at subverting such rules. These indigenous painters found cunning ways to covertly resist this overt repression:

Restricted to religious imagery, these painters found ways to insert their Andean reality into the paintings; they filled the Garden of Eden with Peruvian birds and flowers, placed a cuy (guinea pig) front and center on the table of the Last Supper (“The Last Supper”), and brought llama herders to the manger in adoration of the Baby Jesus (“Adoration of the Shepherds”). By remaking the biblical world in their image, they placed their own world secretly at its center.

I first encountered Odi Gonzales’ poetry when I read Almas en pena, a collection of poetry that submerges the reader in the rich, syncretic world of the Andes. Born in Cusco and bilingual in Spanish and Quechua, Gonzales is a poet who walks in two worlds and speaks the language of each. In Almas en pena, he maps out for us the terrain of the Andean underworld and speaks in a multiplicity of voices–shamans, priests, wandering souls, animals, demons, angels, and apus. In Birds on the Kiswar Tree, we hear from the angel Baradiel, from the salt miners and llama herders who stare at the Baby Jesus, from the repressive Council of Lima, from the European artists who came to Peru to spread Catholicism, from modern day art critics, from Saint Joseph, and, most importantly, from the indigenous painters themselves. This ability to create a sort of polyphonous poetry, where many voices are represented and coexist, makes him the perfect poet to give voice to the anonymous artists of the Cusco School.

In “The Painter/His Early Works,” one of these poets speaks to us,

In giving words to these silent (and silenced) artists, Gonzales creates what translator Lynn Levin calls a “living and talking museum.” And, in some ways, this work is doubly translated. Gonzales translates from the visual language of these stunning paintings into a rich and textured Spanish, adding history, context, and imagination, and Levin renders that Spanish, carefully and respectfully, into English. This is no easy task, and one that clearly required a great deal of research, but Levin’s endnotes are an immeasurable help to English speaking readers who are not familiar with Andean culture, history or geography. In the end, these poems are both deeply seated in a specific historical and cultural context, and surprisingly universal. As Levin reminds us in her introduction, they “speak to anyone who lives or, historically or imaginatively, has lived under a repressive regime and who seeks a means of artistic resistance.” And while these paintings were indeed repressed, their inappropriate or heretical elements sometimes literally painted or plastered over, Gonzales’ poetry allows us to see them clearly again, and in a new light. In Birds on the Kiswar Tree, art inspires poetry and poetry resurrects art, and, in so doing, gives us back a valuable piece of history.

POETRY INTERNATIONAL: Reviewed by Grace Cornell Gonzales, 2015